MEMORIA

(2021)

“They arrested us and my husband ran up to me to get a divorce.

That was the only way he could save himself.

They sent me and my whole family into exile in an agricultural cooperative. As soon as we arrived, a worker came out of the rooms that had been assigned to us and stealthily passed us a note:

“I mounted a microphone in the bathroom, be careful. I’m sorry”.

I remember that we looked at the written message in complete silence. We had no idea if his warning was gesture of humanity or a trap of the Sigurimi. The only thing we knew for sure was that we no longer felt safe even when we were alone in the intimacy of our family.

This was how the system worked: if things were going well, you were afraid of losing everything for one wrong word; if things were going bad, you were afraid that any little slip could make your situation much worse. And in some cases, like what happened to me, families fell apart.

Family members denounced each other either out of fear, or to protect those who remained.

My own father begged us to condemn him publicly and pleaded with us to do it for our own good. “

Vera Bekteshi, writer

EXCERPT FROM INTERVIEWS MADE BY CHRISTIAN ELIA

From 1945 to 1991, Albania was the biggest prison in Europe.

For forty-five years, during the regime of Enver Hoxha – leader of the Albanian Labor Party and founder of the Albania’s Republic – thinking freely and expressing one’s own opinion in public was irresponsible and dangerous, even to the listeners.

You couldn’t do it in a bar, or even whisper your thoughts confidencially in the ear of a friend or a family member, behind the protective walls of your own home.

Everyone knew that Enver Hoxa’s eyes and ears were everywhere. They could see and hear everything, even your dreams. Everyone knew it was Hoxa who determined what was safe to say, or think or even to dream.

Daily life followed the rules imposed by a comprehensive and efficient surveillance system that insinuated itself into every facet of the public and private lives of all the citizens.

It was a mechanism based on mutual control that used denunciations, interrogations, public trials and punishments such as prison, hard labor and exile to stifle any dissent and were often inflicted on the relatives of the alleged perpetrator as well.

The material executor was the Sigurimi (the Albanian secret police). Organized into sections, it encompassed political control, censorship, internal security management, counterintelligence and international intelligence.

Every day hundreds of agents monitored the ‘ideological correctness’ of party members and other citizens alike , spying on them and then classifying each individual based on their most insignificant mannerisms and behaviors. An omnipresent eye frightened the Albanians to the point of guaranteeing their cooperation without having to ask and prompting them to spy on and spontaneously report on even their family members for saying one word too many.

Memoria is the first chapter of Il Grande Padre (The great Father), a long-term ongoing project I started in 2018 in collaboration with the journalist Christian Elia.

It is a narrative journey that offers immersion into today’s Albania in order to explore the implications and consequences of the rise and collapse of a regime, highlighting the scars it has left on the collective memory. It is a research that, using the particular Albanian case, reflects on the relationship between the individual and power throughout the world.

Specifically, the Memoria series collects the rubble of the surveillance system built by Hoxha and exposes the wounds it has left on the collective psyche today.

“When they came to get me, they ransacked my home and burned all the books I owned. Everything was used against me: the music I listened to, the clothes I wore, much of which had been given to me by the tourists that the very same regime had invited in.

They accused me of being ‘dangerous like the plague’, of having infected young Albanians with the evil of the West. And of espionage.

My first trial took place in front of two thousand people. They spat at me, kicked me, threw things at me. The prosecution asked me three times if I loved the party.

Three times I said no. I told him the party was like an apple, red on the outside but rotten to the core on the inside.

They asked me who the worms were, I replied that they were the party leaders.”

Saimir Maloku, Albanian electronic engineer.

EXCERPT FROM INTERVIEWS MADE BY CHRISTIAN ELIA

Interviews with the witnesses of those years gave me the tools to dig into the present in search of the remains of the past, and to decide how best to photograph them, at what distance, and with what intention.

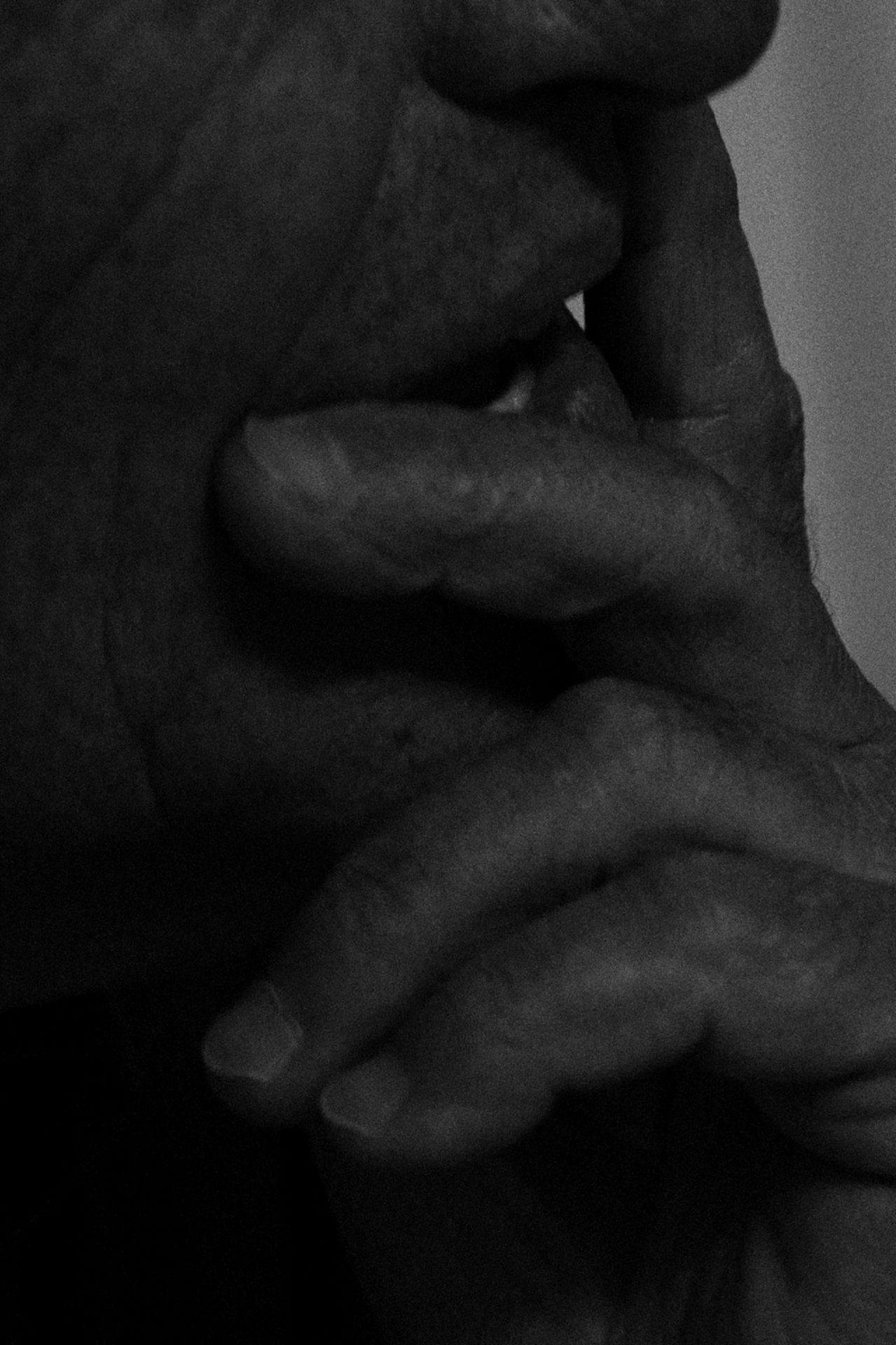

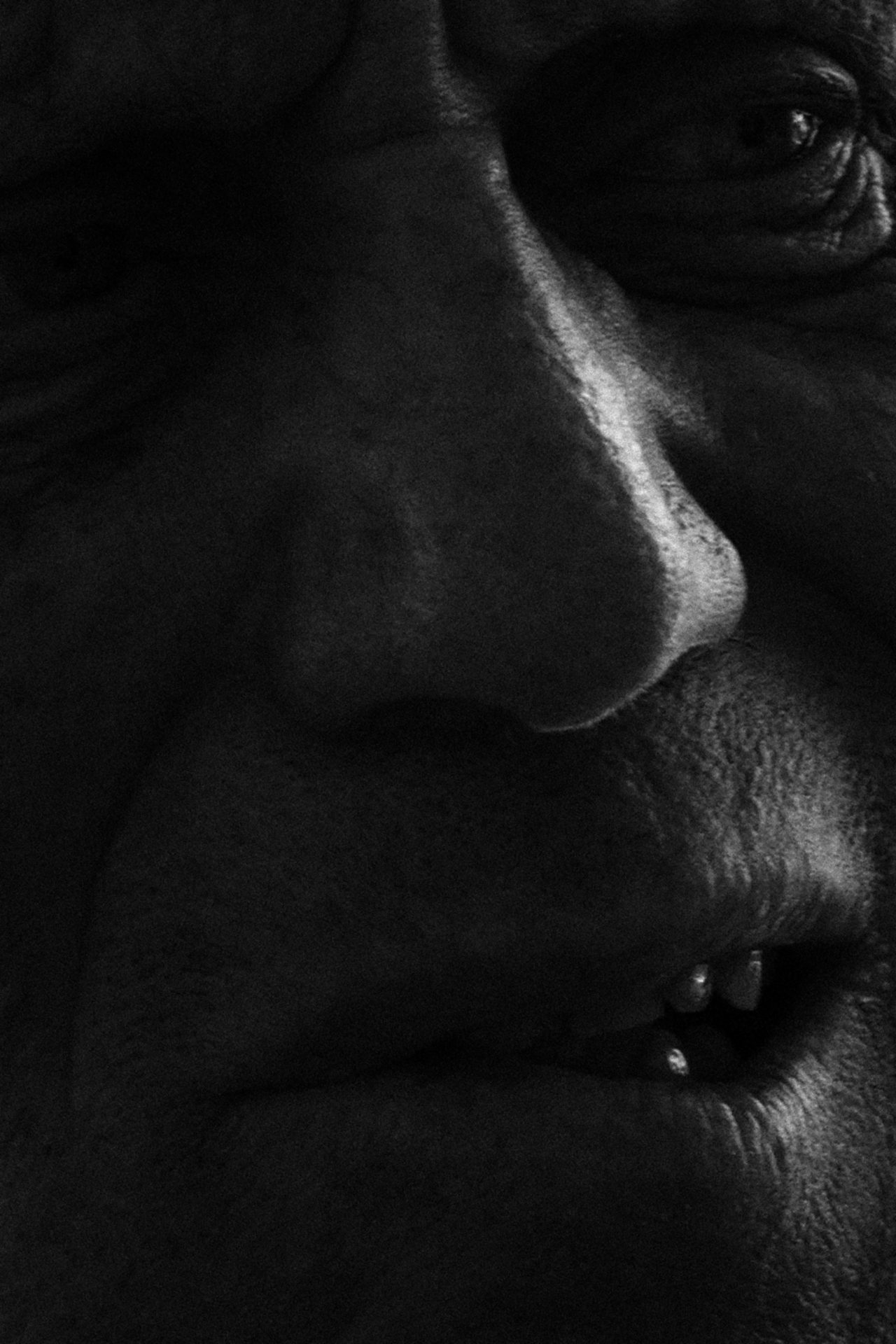

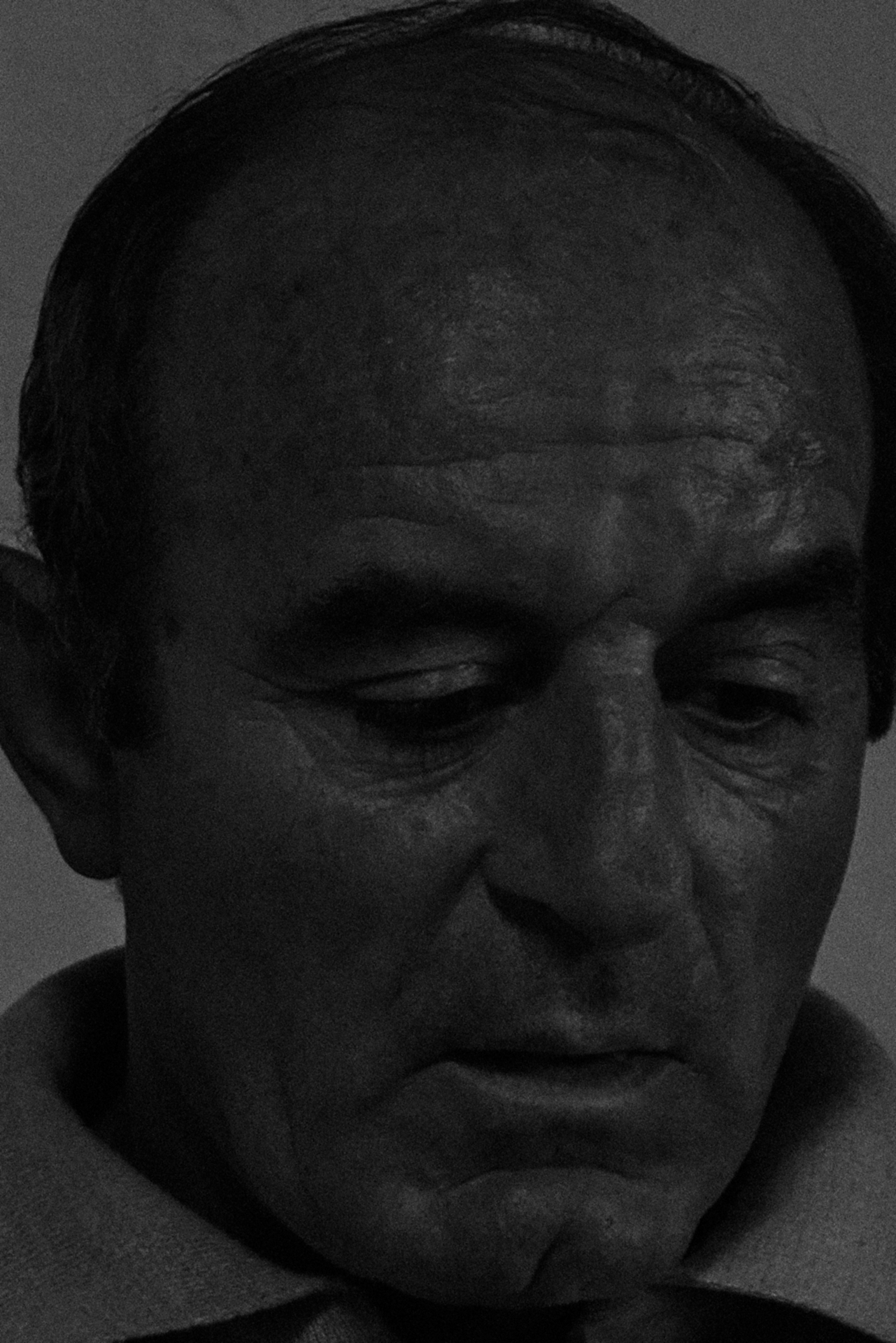

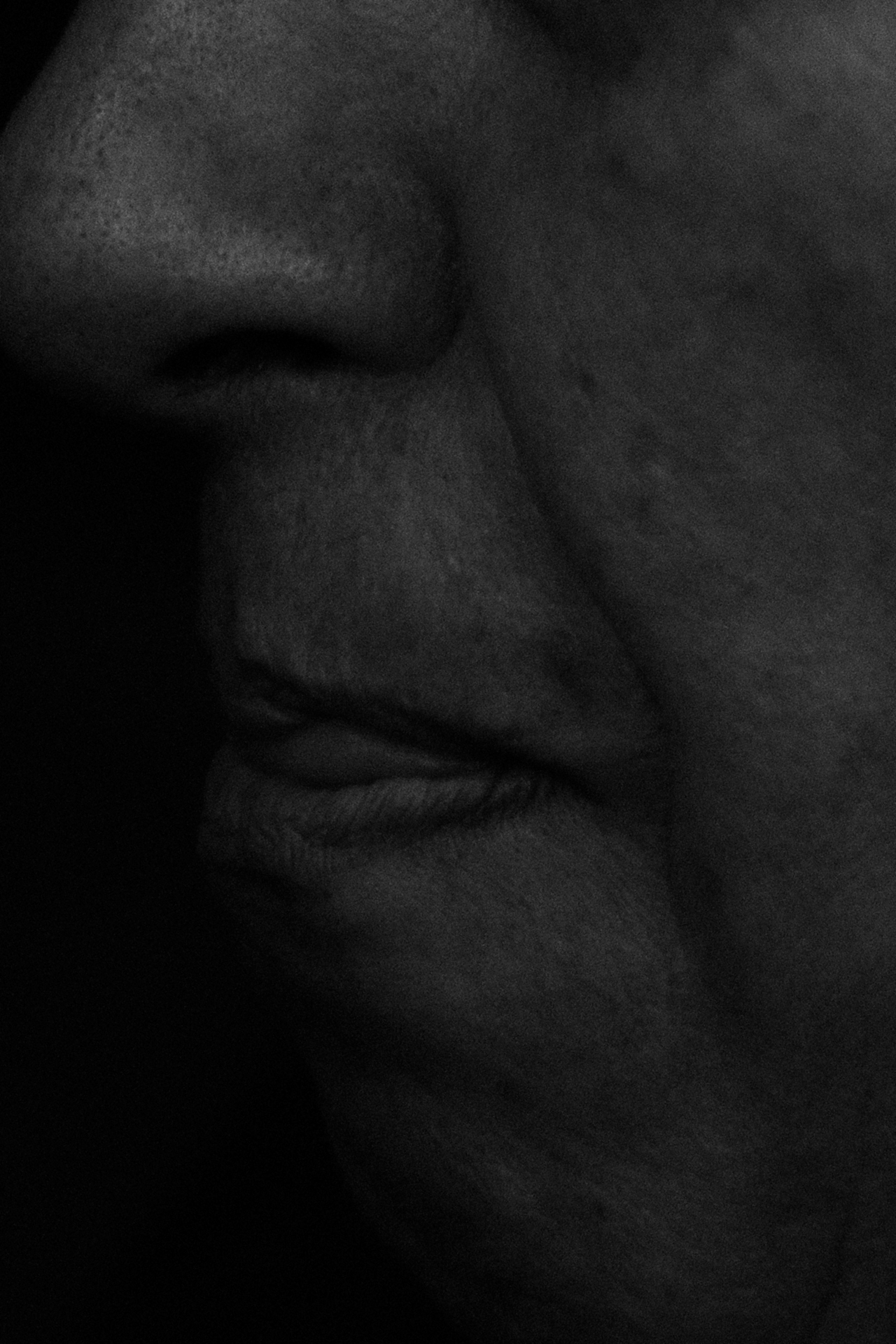

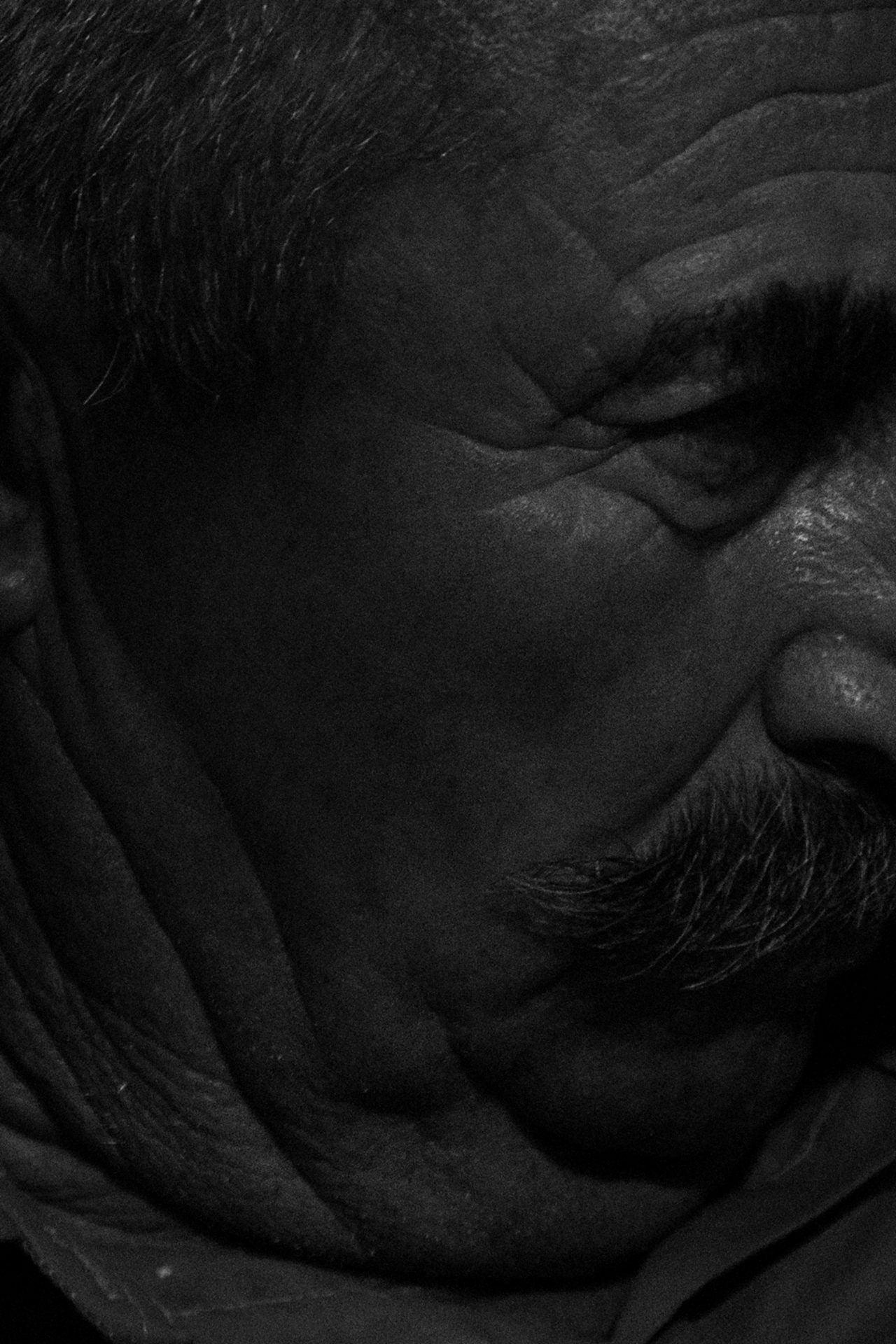

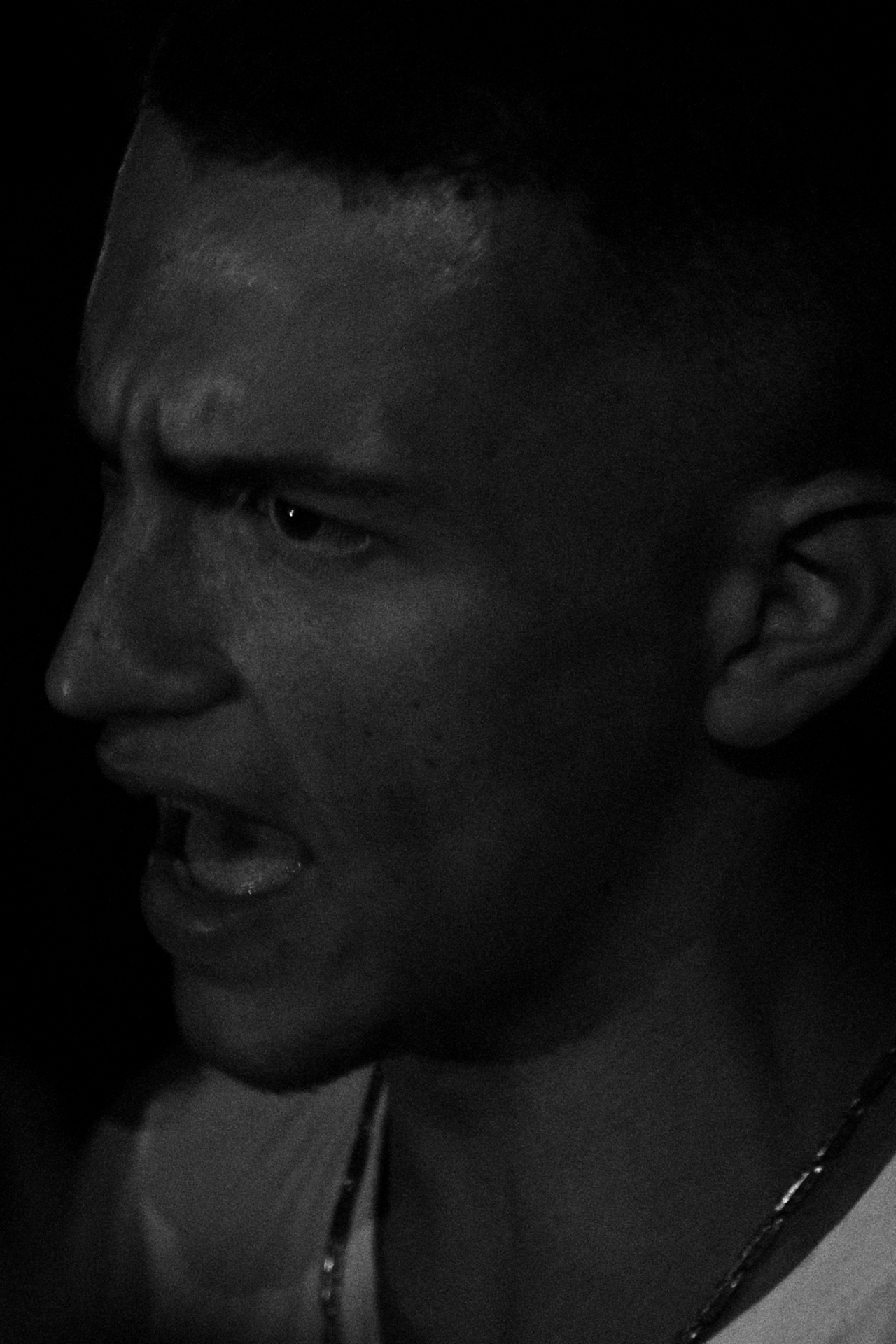

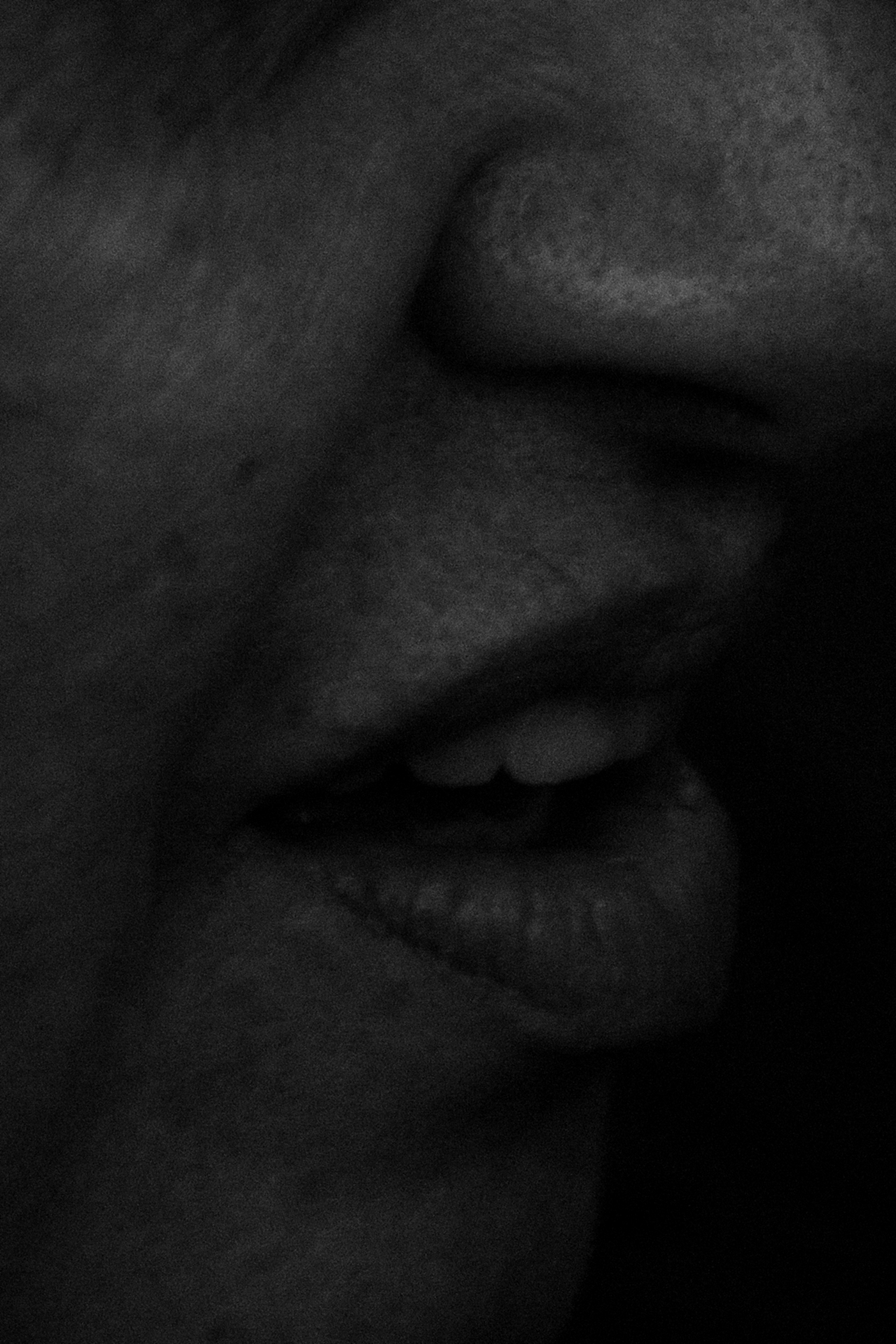

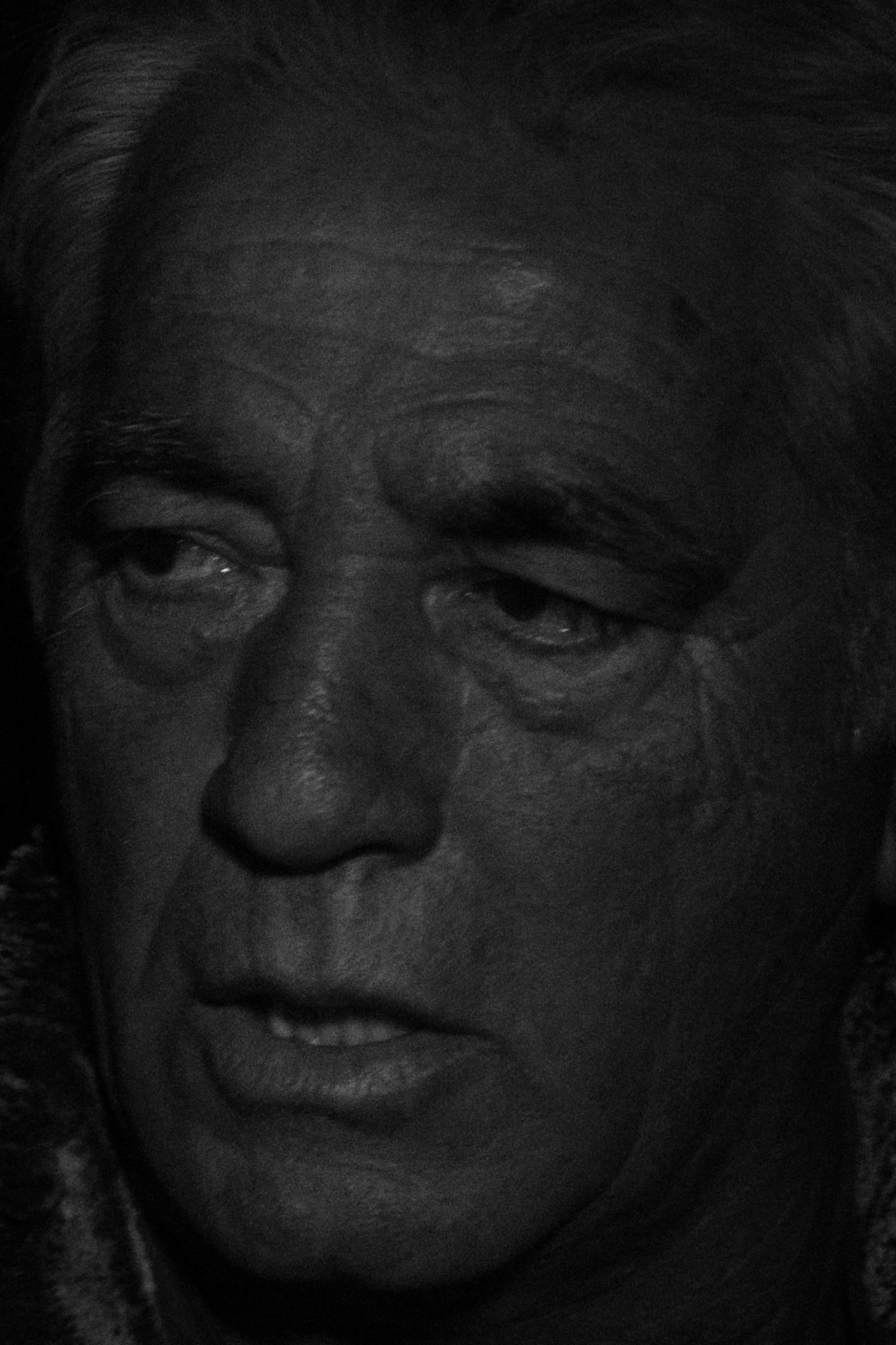

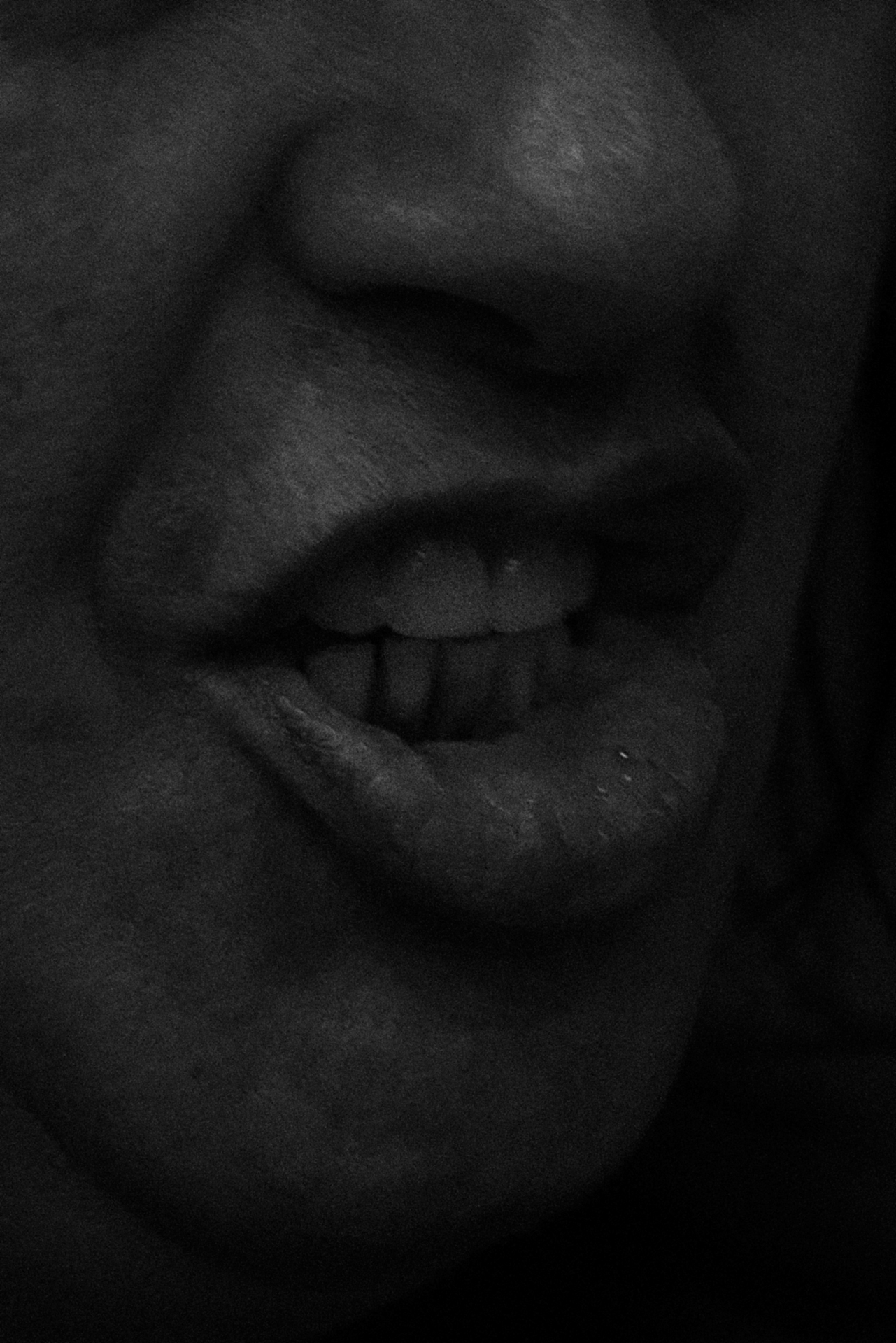

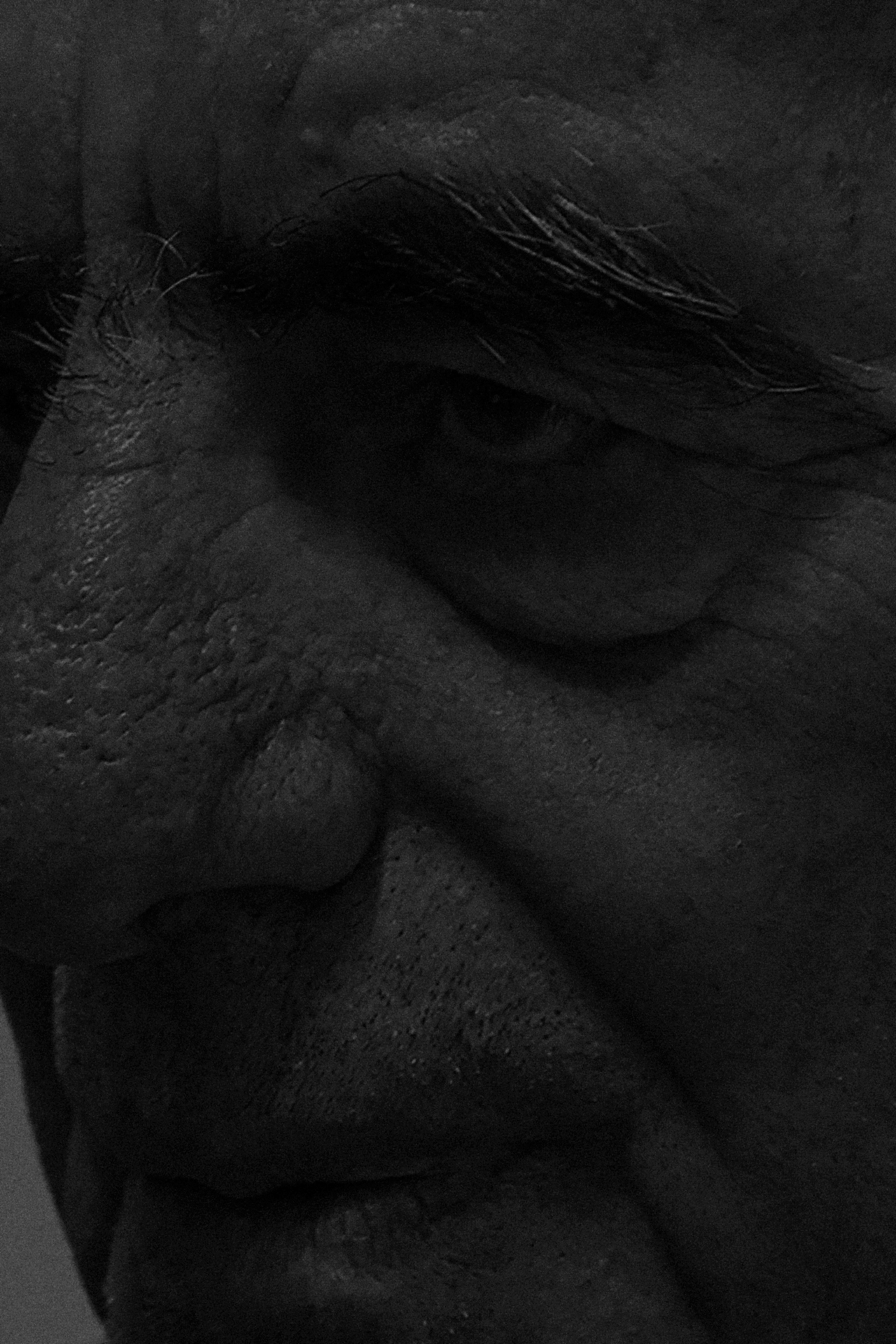

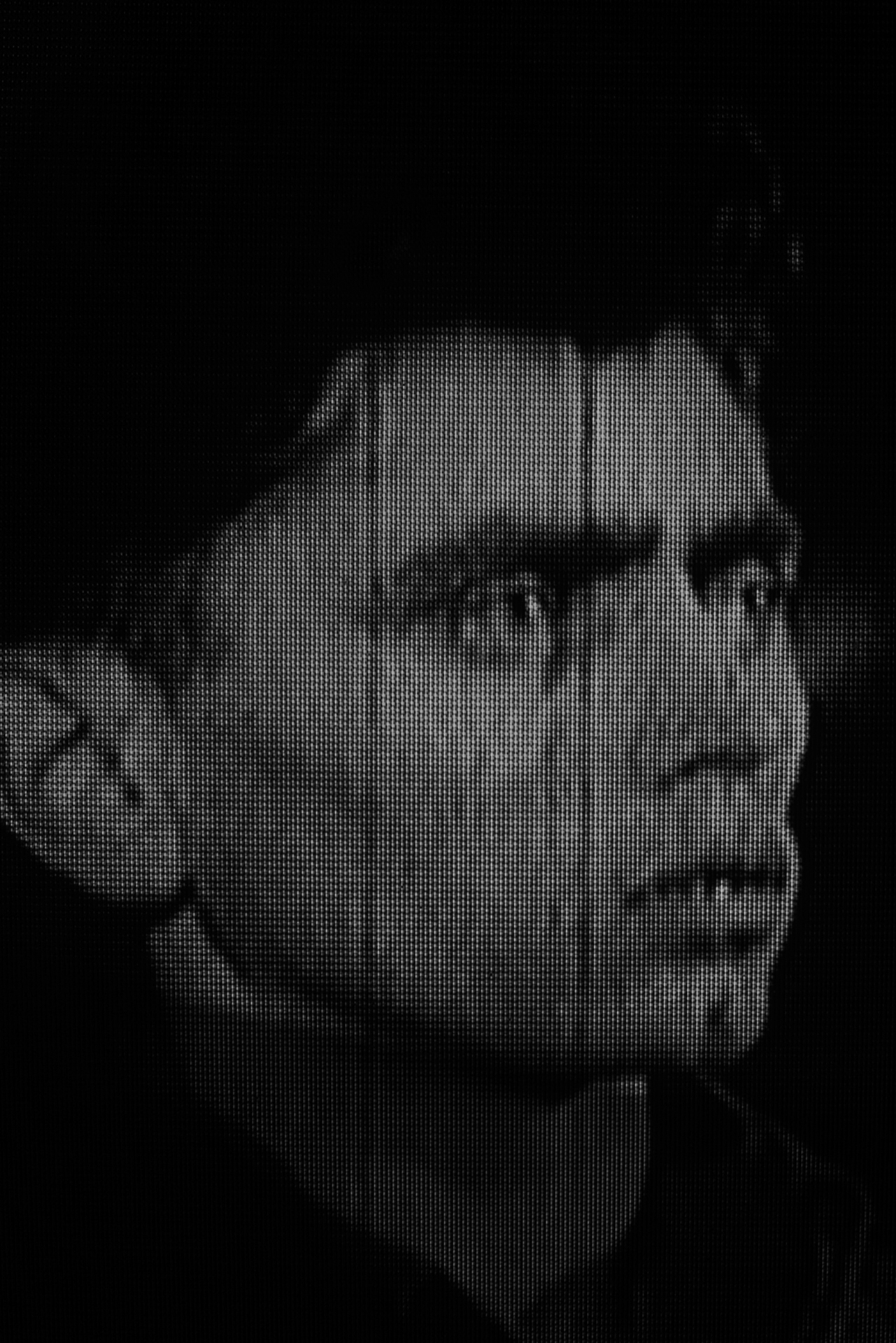

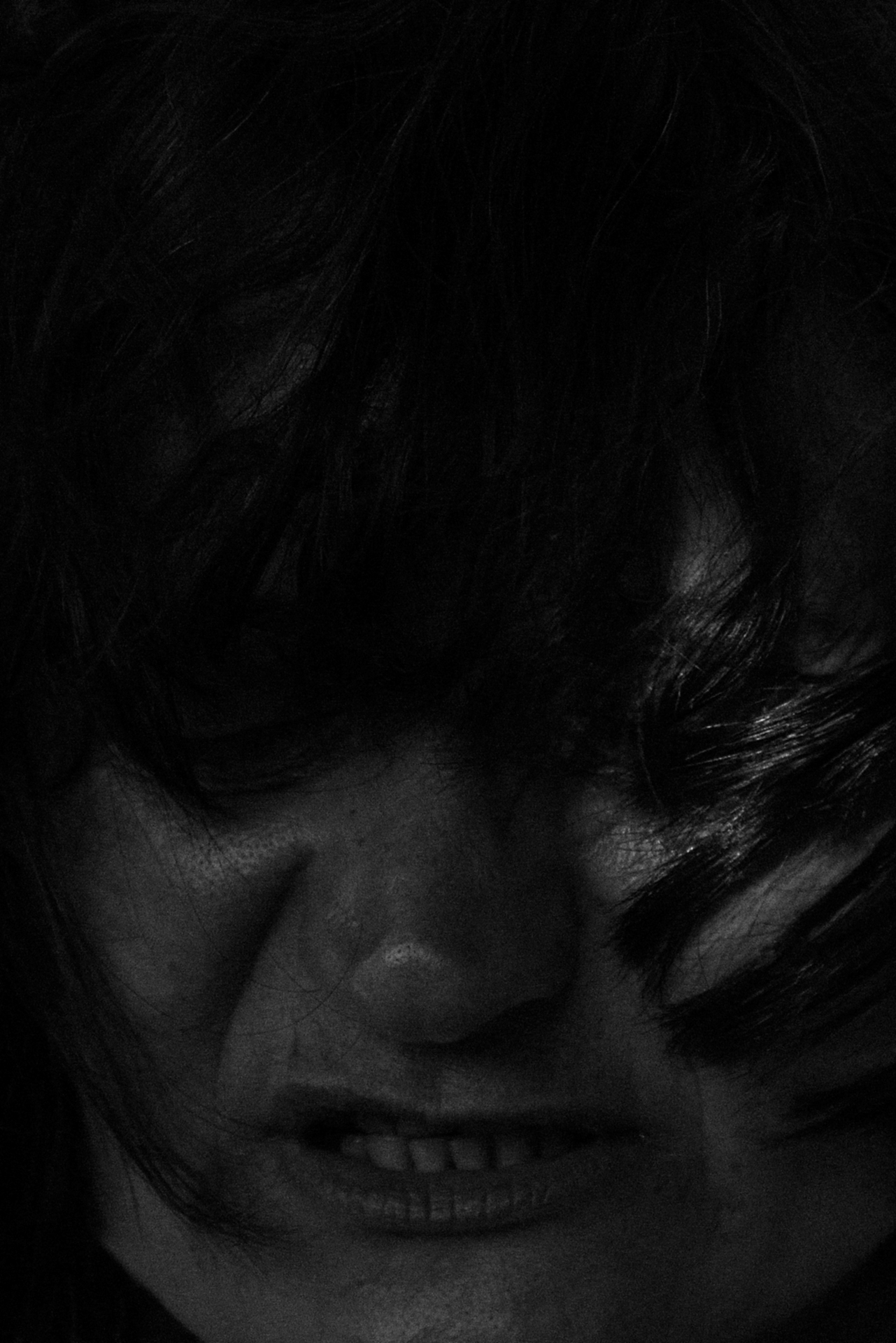

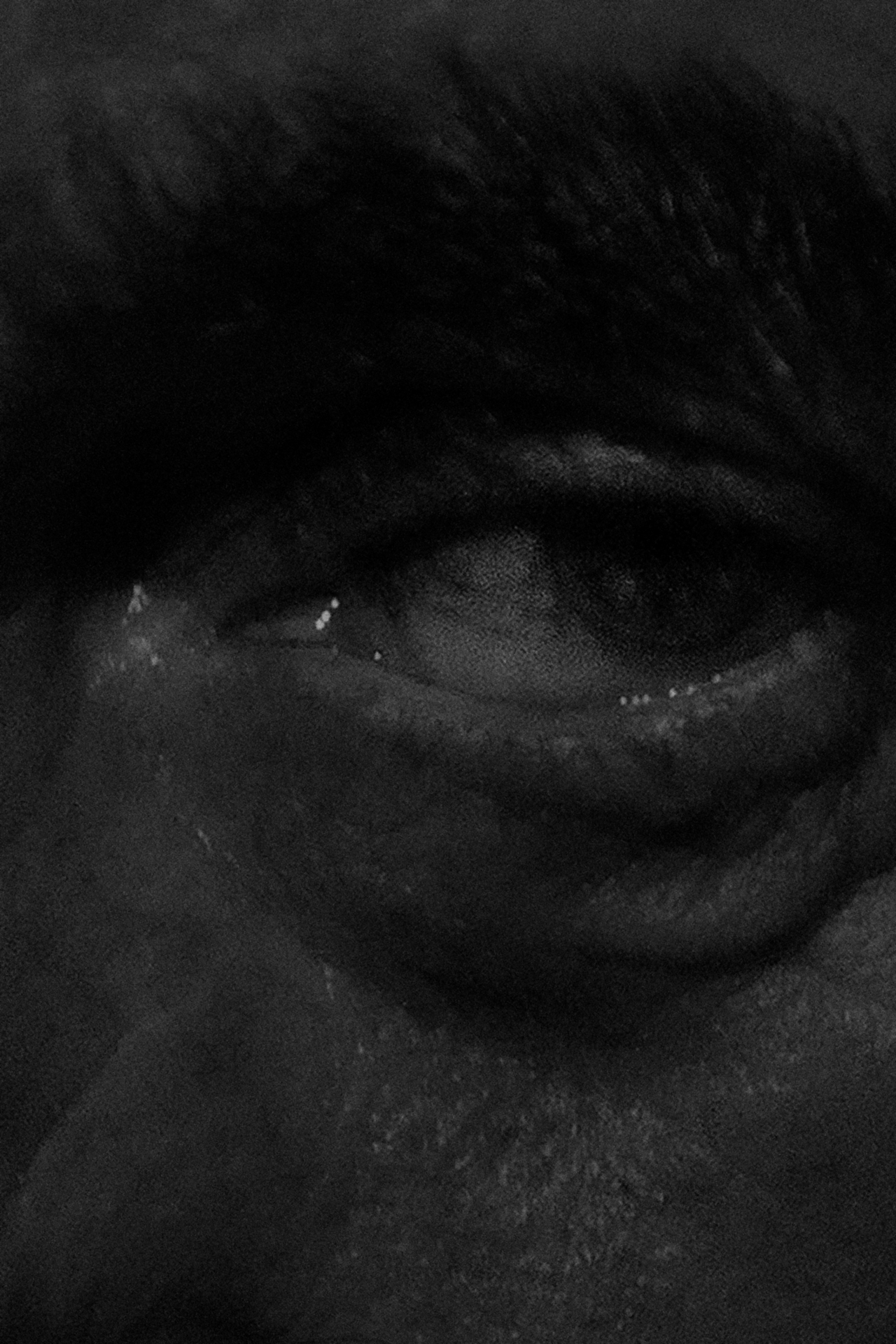

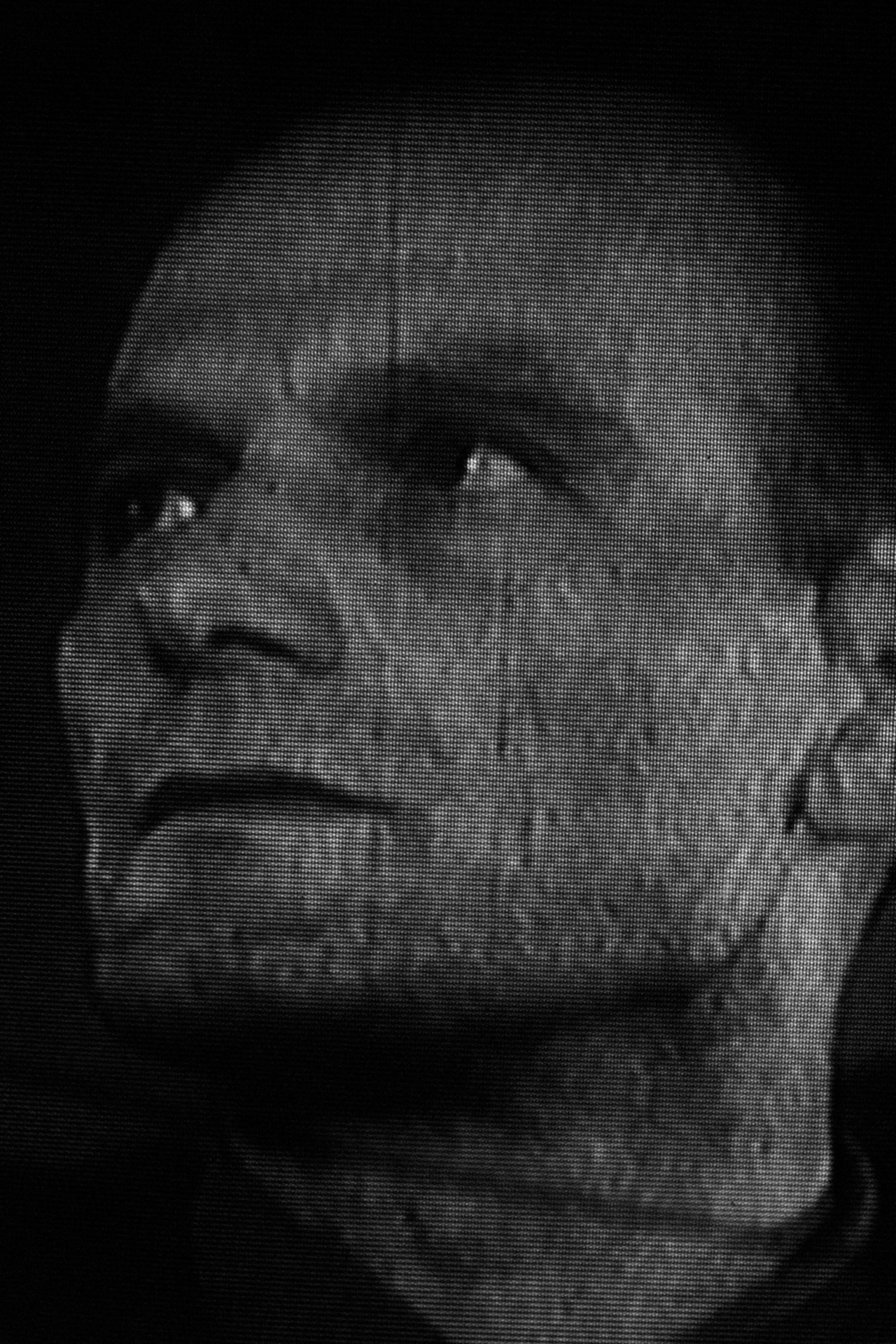

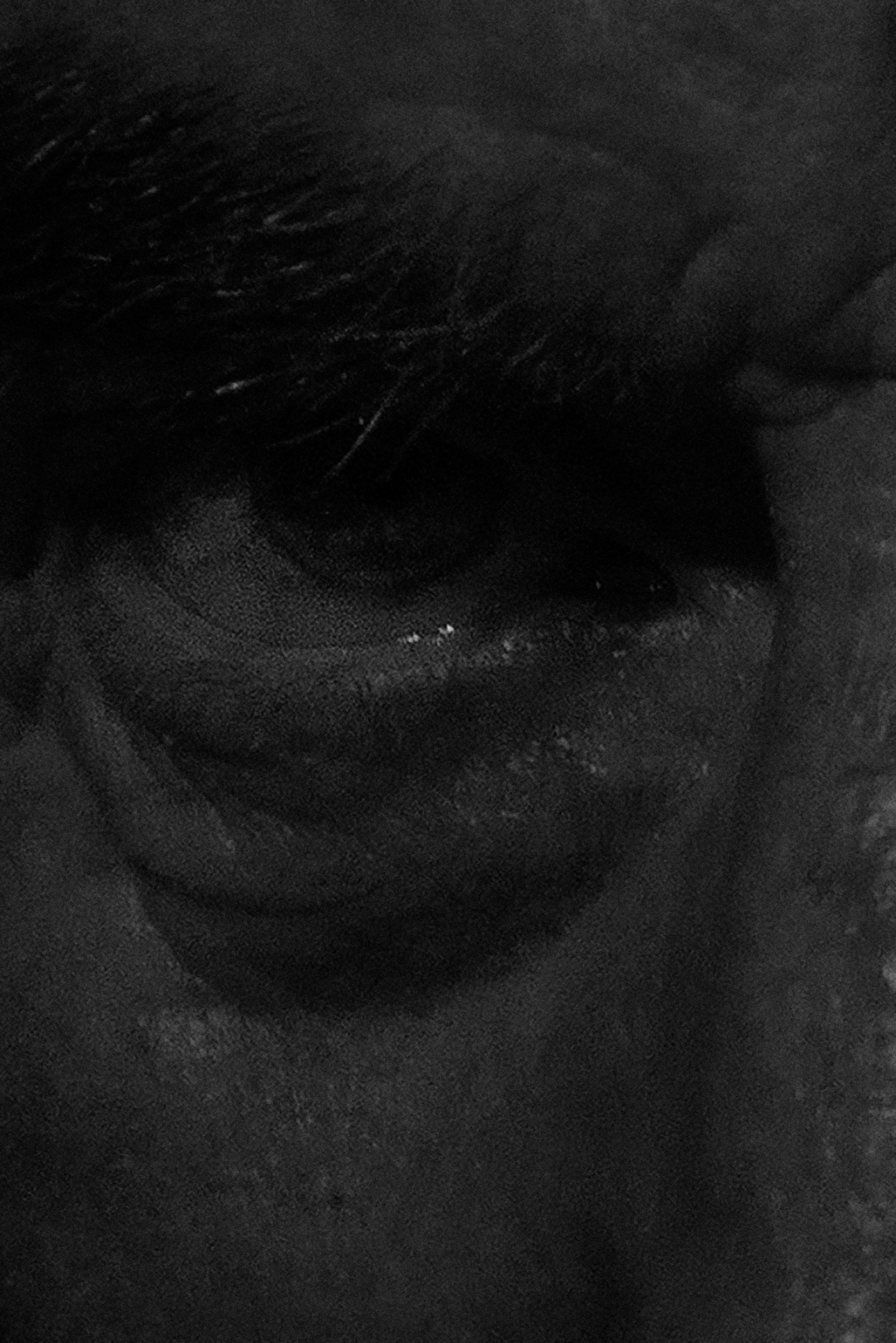

The aesthetics of the propaganda videos that documented the public trials and the many photographs taken by the Sigurimi to spy on Albanian citizens were the reference points for constructing a language to adequately express the suffocating atmosphere that permeated daily life at that time.

The images are of the people I ran into by chance either on the streets of Tirana or in closed spaces. I compelled myself to observe them in detail in search of clues and I recorded their involuntary facial expressions and captured their furtive glances and most insignificant gestures.

The sequence produces a small mutual control network in which the viewer, involuntarily placed in the center of the circle, looks on , and becomes an active participant in the surveillance game.